By Darshini Mahadevia, Renu Desai, Shachi Sanghvi, Suchita Vyas, Aisha Bakde, Mo Sharif Pathan, Rafi Malek*

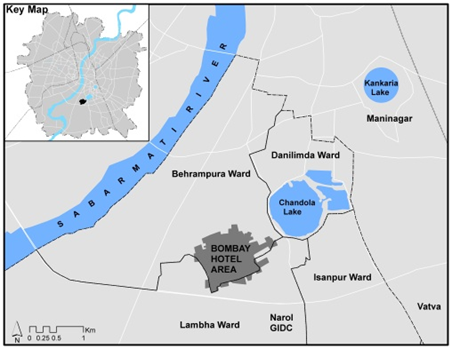

Bombay Hotel is a settlement located next to the Pirana garbage dump on Sarkhej-Narol highway. The residential area of the settlement is spread over about 1 sq.km. and comprises of approximately 25,000 Muslim families. It began to emerge from the mid/late 1990s, but has seen rapid development mainly over the past decade. The settlement is an outcome of the processes that have led to the southern urban periphery, from Juhapura to Ramol, turning into a series of Muslim enclaves. The socio-spatial religious divides intensified after the post-Godhra riots of 2002 as the dominant Hindu population kept Muslims out of most residential areas and communal tensions led Muslims to prefer living in the safety of Muslim enclaves. This also led to the ghettoization of the community in some pockets on the southern periphery, with low-income Muslims concentrating in localities like Bombay Hotel which has developed as an informal commercial subdivision. Here, builders informally bought land from farmers, informally developed it into plots or tenements without any of the requisite development permissions and informally sold these.

This policy brief examines the absence of the welfare state in the locality, the emergence of informal non-state actors in services provision, and finally the dynamics of recent state interventions in services provision to trace the pathways through which deprivations, conflicts and violence emerge and unfold in relation to basic services and infrastructure.

“Poverty, Inequality and Violence in Indian Cities: Towards Inclusive Policies and Planning,” a three-year research project (2013-16) undertaken by Centre for Urban Equity (CUE), CEPT University in Ahmedabad and Guwahati, and Institute for Human Development in Delhi and Patna, is funded by the International Development Research Centre (IDRC), Canada and Department of International Development (DFID), UK, under the global programme Safe and Inclusive Cities (SAIC). The research analyzes the pathways through which exclusionary urban planning and governance leads to different types of violence on the poor and by the poor in Indian cities.

|

| Municipal ward boundaries as of 2014 |

The CUE research takes an expansive approach to violence, examining structural or indirect violence (material deprivation, inequality, exclusion), direct violence (direct infliction of physical or psychological harm), overt conflict and its links to violence and different types of crime. We note that not all types of violence are considered as crime (for example, violence by the state), and not all types of crime are considered as violence (for example, theft).

In Ahmedabad, the largest city of Gujarat state, the research focuses on two poor localities: Bombay Hotel, an informal commercial subdivision located on the city’s southern periphery and inhabited by Muslims, and the public housing sites at Vatwa on the city’s south-eastern periphery used for resettling slum dwellers displaced by urban projects.

|

Builders acquired agricultural land from farmers and in order to save time and money, they developed this land for residential societies without taking permission from the state to convert this land for non-agricultural (NA) use. Further, the builders acquired the land through stamp papers (i.e. sale agreements which are not registered sale deeds) or Power of Attorney documents, and then sold the tenements/plots through stamp papers. Therefore, the land still legally belongs to the farmers as per the government land records such as the 7/12 documents. The builders and residents have also not taken any of the other requisite development permissions such as No-Objection Certificates (NOCs) before constructing and occupying tenements on this land.

These informalities in Bombay Hotel, the non-payment of property tax by most residents, and the absence of sanctioned Town Planning (TP) Schemes for the area have been cited by the Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation (AMC) as the main reasons for its non-provision of municipal services and amenities in the locality. This absence of the welfare state has created a vacuum in which informal non-state actors have emerged and consolidated their role as services providers. Dependence on these non-state providers for services has generated various forms of conflicts and violence that has become a part of the everyday experiences of the residents.

The Relationship between Informal Services and the State

Along with informally laying out plots or constructing tenements in the residential societies, many of the builders had also put in some infrastructures such as bore-wells and soak-pits or drainage lines. They appointed an operator to supply bore-well water to the residents. Besides them, local goons and powerful residents also began to capitalize on the absence of the welfare state by turning into service providers.The importance of all these informal providers escalated in the locality over the next several years as a result of the vacuum created by the continuing absence of the welfare state. Significantly, many of the informal providers draw their power and authority from muscle-power and links to political actors, some of whom are part of the local or regional state. This is also why not everyone can construct a bore-well and turn the scarcity of water in the locality into a business opportunity. Usually, only those with connections to politicians and/or goons are successful in being a part of the bore-well enterprise in Bombay Hotel.

Moreover, the ability of such a large and informal apparatus of service delivery to sustain itself would be unlikely without the covert compliance of the state. A municipal official said that the AMC is aware of the large number of bore-wells in Bombay Hotel but does not do anything about this unregulated groundwater extraction and sale since it cannot provide adequate water in the locality. In fact, AMC is also aware of the contaminated water being supplied to residents from these bore-wells since it had collected water samples from the locality after some residents died due to consumption of contaminated water (no action was taken by the AMC after taking samples). Some residents also speculate that there is a nexus between the local state and the bore-well owners and one of the reasons that the AMC does not provide municipal water supply to the locality is because this would destroy the latter’s lucrative business.

Informal service delivery in localities like Bombay Hotel would not be possible without the covert compliance of the state. Municipal officials are aware of the large-scale unregulated groundwater extraction and sale in the locality, and are also aware that this is contaminated water and is being consumed by large numbers of people. And yet the municipal government did nothing about this for several years.

In the case of electricity provision, illegal electricity providers have sources at Torrent Power, the private company that supplies electricity in the city, who tip them off before a raid is to be conducted in the locality.

LOGICS AND MODALITIES OF INFORMAL SERVICE PROVISION, LEADING TO DEPRIVATIONS AND CONFLICTS

The dynamics around informal provision and access to water is the biggest source of deprivation and conflict faced by the residents of Bombay Hotel. Conflicts occur between residents and water providers as well as amongst residents. Poor drainage conditions created by the informal drainage provision lead to health issues as well as conflicts between residents. Conflicts also occur in the context of illegal electricity supply, mainly between residents and the suppliers over payment of monthly charges.

Territoriality in Water and Electricity Provision

Informal suppliers in Bombay Hotel work within rigid territorial boundaries especially in the provision of water and electricity. Bore-well owners supplying water to residents of one society would not supply water to residents of another society. There is an understanding among the bore-well owners in this regard so that they can protect their profit margins. As a result, if a resident is getting inadequate water from her bore-well operator or has had an altercation with him/her then she cannot easily switch to another operator. This has laid a considerable amount of strain on residents’ access to water as bore-well motors tend to break down rather frequently, especially during the summer when the water tables are low, because of which they do not get water for days at a stretch. In fact, the territoriality often forces residents to stay mute on the exploitation by their bore-well operator as complaining about this could lead to discontinuation of their water supply. Many residents have even been warned by their bore-well operators against filling water for their friends or relatives from other societies as it would lead to disconnection of their own supply. Water from the bore-wells is supplied for only 15-20 minutes every alternate day and is insufficient to meet the requirements of the residents.

Profit Motives and Unregulated Service Delivery Mechanisms

The motive of the informal non-state actors in the provision of crucial services such as water, drainage and electricity is purely profit-oriented and they have little concern for the well-being and safety of the residents.The informal water suppliers rake in profit by levying a monthly charge of Rs.200-250 on residents but the water is of poor quality (the presence of industries and the garbage dump has contaminated the ground water) and often irregularly supplied. When the bore-well motors breakdown, some of the water suppliers collect money from residents to repair them. The water from the mosques in the locality that supply water from their bore-wells to residents in adjoining areas is also of poor quality. Moreover, the mosques claim that the profit generated from the water supply is used for the maintenance and upkeep of the mosque, however, in some cases, this profit has been privately (mis)appropriated by one of the mosque’s functionaries.

Informal non-state actors have made money by charging residents for putting in drainage infrastructure and beyond this, they take no responsibility for the proper functioning and maintenance of this infrastructure. For instance, the builders who had initially provided soak-pits that were to be shared among 4-5 households did not pay any attention to their longer-term maintenance and simply connected these illegally to the private drainage lines of the surrounding industries. As a result, the soak-pits and drains, unable to withstand the burden of the increasing population in the locality, started overflowing frequently and created an unsanitary environment in the locality. This has also led to fights between residents who have had to incur regular expenses of calling in private cleaners to empty the soak-pits and clean the guttters. Solid waste that is removed from the gutters is also a source of conflict between residents as most of it is simply dumped on the streets or in one of the lakes within the area. There have also been instances of children losing their lives after falling into open drains that are scattered across the locality. Furthermore, sewage water from the overflowing drains seep into the bore-wells, contaminating the water and endangering public health.

Torrent Power supplies electricity in the locality under its scheme for slums but the tariff is still too high for many residents and sometimes the bills seem to be higher than what they should be given the electricity consumption. Many residents are also unable to afford the high costs of installing a meter. Most residents therefore turn to illegal electricity suppliers who charge a monthly amount of Rs.200-250. Those who use appliances such as sewing machines that consume more electricity are charged a little more. While these charges are much lower than for formal electricity from Torrent, the illegal electricity suppliers have no concern for safety. Several residents, especially young children, have been injured after coming in contact with live wires left unattended to by these suppliers.

In one of the societies, a local leader complained to a politician about the poor quality of water being supplied by the bore-well operator. This angered the operator who then stopped supplying water to the residents which in turn led to an argument between the residents and local leader as the former felt that the latter should not have complained to the politician as this had totally cut off their access to water.

Torrent Power supplies electricity in the locality under its scheme for slums but the tariff is still too high for many residents and sometimes the bills seem to be higher than what they should be given the electricity consumption. Many residents are also unable to afford the high costs of installing a meter. Most residents therefore turn to illegal electricity suppliers who charge a monthly amount of Rs.200-250. Those who use appliances such as sewing machines that consume more electricity are charged a little more. While these charges are much lower than for formal electricity from Torrent, the illegal electricity suppliers have no concern for safety. Several residents, especially young children, have been injured after coming in contact with live wires left unattended to by these suppliers.

In one of the societies, a local leader complained to a politician about the poor quality of water being supplied by the bore-well operator. This angered the operator who then stopped supplying water to the residents which in turn led to an argument between the residents and local leader as the former felt that the latter should not have complained to the politician as this had totally cut off their access to water.

Coercive Practices

Many of the informal suppliers in Bombay Hotel adopt violent practices and behavior in their dealings with the residents. Lack of alternatives reinforces the vulnerability of residents who are forced to put up not only with economic exploitation of the suppliers but also coercion, threats and abuse. Many residents earn daily wages and may not always be able to pay the monthly charges to the suppliers on time. This leads to warnings from the supplier and threats that their water / electricity connection would be cut. One woman resident referred to the water operator’s behaviour towards residents as “shabdik atyachaar” (verbal torture). The feeling among women residents of being abused by the water operators is exacerbated by the fact that the latter are often under the influence of alcohol or drugs when they come to collect the monthly charges from them. |

| Water-logging due to poor drainage |

DYNAMICS OF STATE INTERVENTION IN THE PROVISION OF BASIC SERVICES

In 2004, the AMC provided some basic services to a society in Bombay Hotel called Citizen Nagar. This was in response to an order by the Supreme Court on a PIL filed by the Antrik Visthapit Haq Rakshak Samiti (AVHRS) on behalf of the rehabilitated victims of the 2002 riots. A road was paved, connecting Citizen Nagar to the main road. This ended up also benefiting the residents of some of the other societies. Thereafter, other basic services such as drainage lines and water tankers were also provided to the residents of Citizen Nagar.

NGOs such as Sanchetana and Centre for Development (CfD) have also played an important role in mobilizing residents of Bombay Hotel to demand basic services as well as social infrastructure (municipal school, anganwadis, etc).

Marginalized Citizens and Access to the State

Attempts made by the residents to approach the state for services demonstrate the bias of the state against localities like Bombay Hotel. Visits to AMC by certain residents concerned about and impacted by the poor quality of life in Bombay Hotel were met with hostility by government officials for several years. One local leader said that when he had gone to the AMC office some years ago to ask municipal officials to address the solid waste issues in the locality, he was pushed out of the office. Another local leader said that he had been told by a politician of the Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP), which has been in power at the city-level since 2005, that the party had not allocated any funds for development work in the locality. Such residents opine that the AMC did not provide services for many years because it is a Muslim locality.NGO Advocacy

In 2004, the AMC provided some basic services to a society in Bombay Hotel called Citizen Nagar. This was in response to an order by the Supreme Court on a PIL filed by the Antrik Visthapit Haq Rakshak Samiti (AVHRS) on behalf of the rehabilitated victims of the 2002 riots. A road was paved, connecting Citizen Nagar to the main road. This ended up also benefiting the residents of some of the other societies. Thereafter, other basic services such as drainage lines and water tankers were also provided to the residents of Citizen Nagar.

NGOs such as Sanchetana and Centre for Development (CfD) have also played an important role in mobilizing residents of Bombay Hotel to demand basic services as well as social infrastructure (municipal school, anganwadis, etc).

|

| Media coverage of protests against lack of basic services |

Local Leaders, Political Patronage and Clientelism

Lack of direct access to the bureaucracy has led to the dependence of the residents on local leaders and politicians to mediate with the state on their behalf. Despite being marginalized citizens, some residents have developed connections with local municipal officials over time through persistent efforts, also emerging as local leaders in the process. Immense time and effort goes into establishing these networks and local leaders at times make substantial financial investments towards these processes as well. The recent re-drawing of municipal ward boundaries which has brought some pockets which were in Lambha ward into Behrampura ward has not been welcomed whole-heartedly by the local leaders in these pockets because the contacts and networks they had established in the former ward with much difficulty are now of little use to them.Local leaders have also played a major role in mobilizing residents to demand basic services through rallies and protests to municipal offices. However, these have often not yielded any action from the AMC.

“Three years ago, people took out a rally to demand gutter lines. All of us went to the corporation office and created a huge noise, broke our water pots there. However, nothing came of this.”

The inability / unwillingness of AMC to provide services in spite of these protests created a space for politicians to mediate between the residents and the state. Most of the residents attribute the introduction of basic services by AMC to the efforts of Badruddin Sheikh, the local councilor in Behrampura ward (since 2010) and Shailesh Parmar, the MLA (since 2012), both belonging to the Congress Party. Over the last five years, these politicians have used their budget to fund development works in the locality such as road paving in some societies, the construction of drainage lines in some internal lanes, and provision of some streetlights.

However, this has resulted in a double-edged situation. Since politicians depend on the locality for votes and the residents depend on politicians for accessing basic services from the state, this political patronage and clientelism does bring in essential services in a situation where the locality is otherwise ignored by the state. However, it also leads to uneven development across the locality as the politicians intervene in areas with local leaders linked to them. Areas within Bombay Hotel without any strong and networked leadership struggle to a greater extent to access the state.

Unevenness in basic services provision in Bombay Hotel is also reflected in the case of water supply through municipal tankers. Municipal water tankers have been allocated to Bombay Hotel by the mediation politicians due to the struggles faced by residents to obtain safe and adequate drinking water. However, at present, the tankers provide water which is adequate for only 3.5 per cent of the population, thus generating another set of conflicts between residents because of the limited supply. The tankers only visit some localities, creating deprivation in some pockets that ultimately rely on the contaminated bore-well water for consumption.

“Sometimes there are bad fights. A few days ago two women physically attacked each other and pulled each other’s hair. We had to call the police. One woman was sent to the hospital and the police arrested the other woman. Women fight with each other because only one tanker comes here for so many people and we cannot be certain that each of us will get water.”

Some local leaders have taken the initiative of maintaining queues at the water tankers, but they also often siphon off extra water for themselves or allow their friends or relatives to take more water than the others.

Planning and Informality

One of the reasons for the absence of basic services in Bombay Hotel is the delay in the implementation of the two Town Planning (TP) Schemes, 38/1 and 38/2. (See Policy Brief 1 for a detailed discussion on the TP Schemes)As a result of the TP Scheme delays, the scale of informal development within the locality expanded between the time the land surveys for the TP Schemes were conducted (2003-2004), the draft TPs were sanctioned (2009 and 2006, respectively) and the TP implementation began (end of 2013). Therefore, a large number of houses now find themselves located on land reserved for infrastructure and amenities under the TP Schemes. Furthermore, a closer look at the TP Schemes also reveals that a large proportion of land has been reserved for roads. Allocation of a significant proportion of land for the sale of residential and commercial in an area inhabited by residents of a lower socio-economic status is also questionable.

The impact of reserving plots on a large scale in a locality which has already developed informally is that this has resulted in a large number of households not being eligible to receive basic services as they are occupying these reserved plots. They are also not eligible to receive the No-Objection Certificates issued by the AMC for residents living in houses of less than 40 sq m area nor can they apply for the regularization of their illegal construction under the Gujarat Regularization of Unauthorized Development Act.

The ongoing implementation of the TP Schemes has also posed challenges for the residents in accessing basic services. For instance, the drainage lines that are being laid across the locality have made it difficult for water tankers to enter societies. As a result of this, the tankers arrive on open grounds in some common areas which lead to conflicts between residents of different societies. In another case, residents whose properties were affected during demolition for laying drainage lines and road widening also lost their Torrent Power electricity meters. When they tried to negotiate with Torrent Power for new connections, they were asked to pay the entire cost of installing the meters once again, which was unaffordable for most of them given their economic conditions.

Through TP implementation while AMC has initiated the process of providing basic services by laying drainage lines as well as constructing a water storage tank to provide municipal water to the locality, it does not prioritize the provision of social infrastructure such as schools, health-centres, and parks/gardens as it argues that it is a cost that the community would have to bear for having “encroached” upon reserved plots on which the amenities were to be provided. Lack of social infrastructure would have a direct impact on the quality of people’s lives and for availing of opportunities required for upward mobility.

POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

# Fast-track the TP Schemes to provide basic services and amenities to Bombay Hotel’s residents. However, it is also essential that modifications are made in the design and implementation of the TP Schemes and this is done in a sensitive, transparent and participatory manner. The demographic and socio-economic conditions of Bombay Hotel are significantly different now as compared to when the surveys for the TP Schemes were undertaken in 2003-2004. There is a need to update the existing data so as to provide an adequate level of basic services and amenities to the residents of the locality. The design and implementation of TP Schemes should include inputs of the residents, local leaders as well as address specific needs of women and children. (also see Policy Brief 6)

# Greater accountability and transparency is necessary in the city-level and ward-level budget-making. This also applies for the funds being earmarked / utilized for development work in each locality, and local leaders as well as residents must have access to such information.

# The expenditures of the local-level elected representatives should also be included in the ward-level budgets since discretionary application of the MP, MLA and Councilor funds only serves to strengthen clientelism, thereby creating uneven development.

Subsidize the costs of providing basic services to poor households and offer a range of payment options.

# Greater accountability and transparency is necessary in the city-level and ward-level budget-making. This also applies for the funds being earmarked / utilized for development work in each locality, and local leaders as well as residents must have access to such information.

# The expenditures of the local-level elected representatives should also be included in the ward-level budgets since discretionary application of the MP, MLA and Councilor funds only serves to strengthen clientelism, thereby creating uneven development.

Subsidize the costs of providing basic services to poor households and offer a range of payment options.

Research Methods

# Locality mapping and community profiling

# Ethnography + ad-hoc conversations

# 16 Focus Group Discussions (men and women)

# 21 individual interviews (local leaders, water operators, active residents, etc)

# Interviews with political leaders & municipal officials

—

*Prepared by the research team of the Centre for Urban Equity (CUE), CEPT University, Ahmedabad, on “Safe and Inclusive Cities – Poverty, Inequity and Violence in Indian Cities: Towards Inclusive Policies and Planning” . Two of the researchers (Mo Sharif Pathan, Rafi Malek) of this policy brief are from the Centre for Development (CfD), Ahmedabad

Courtesy: CUE, CEPT University, Ahmedabad

# Ethnography + ad-hoc conversations

# 16 Focus Group Discussions (men and women)

# 21 individual interviews (local leaders, water operators, active residents, etc)

# Interviews with political leaders & municipal officials

—

*Prepared by the research team of the Centre for Urban Equity (CUE), CEPT University, Ahmedabad, on “Safe and Inclusive Cities – Poverty, Inequity and Violence in Indian Cities: Towards Inclusive Policies and Planning” . Two of the researchers (Mo Sharif Pathan, Rafi Malek) of this policy brief are from the Centre for Development (CfD), Ahmedabad

Courtesy: CUE, CEPT University, Ahmedabad

Comments