|

By Jag Jivan

There has been considerable hoopla of late around how Gujarat’s health indicators, as found reflected in infant mortality rate (IMR), have suggested a “sharp improvement” recently. There have been reports which claim that there has been 33 per cent improvement in a decade. Indeed, while government officials, such as PK Taneja, state health commissioner, have pointed towards how Gujarat’s IMR has reduced to 41 in 2011 from 60 in 2001 (see HERE), even senior economists such as Prof Bibek Debroy, known to shower praise on the state’s “development model”, have been forced find such claims fake. Prof Debroy admits, “If Gujarat’s benchmark is better performing states, as it should be, and not all-India averages, obviously Gujarat needs to do better” (“Gujarat – The Social Sectors”, October 2012, Indicus White Paper Series). Infant mortality rate is defined as the number of children dying before the age of one. It is counted per thousand.

Despite this admission, unfortunately, Prof Debroy does not seek to provide inter-state comparisons to point towards where Gujarat stands vis-à-vis other states on IMR. What his study fails to mention is that, though Gujarat’s IMR has improved, it is not fast enough to take over states, who too have improved. The data suggest that things remain particularly pathetic in the rural areas. Gujarat’s overall IMR in 2004 was 53, five point lower than the country as a whole – 58. Half of India’s major states performed better than Gujarat. In 2012, for which the SRS released data in September 2013, suggest that Gujarat’s IMR was 38 four points lower than the all-India average of 42, suggesting the gap had narrowed, with the country’s average improving.

Indeed, without doubt, IMR, which the Census of India considers as is an important indicator of the health status of the country (click HERE), has registered a steady decline in India from 58 per 1000 live births in 2004 to 42 per 1000 in 2012. Found reflected in the Sample Registration System (SRS), as part of the exercise carried out by the Office of the Registrar General, India, whose main job is do sample registration of births and deaths in India, the SRS’ IMR data across major states has captured considerable variation between different states, something that has been of keen interest of social scientists and activists wanting to understand how social indicators have been doing across India.

What provides credence to SRS is that it is based on dual record system. The field investigation under SRS consists of continuous enumeration of births and deaths in a sample of villages/urban blocks, followed by independent six monthly retrospective surveys by a full time supervisor. The data obtained through these two sources are matched. The last revision of SRS sampling frame was undertaken in 2004, one reason why, while analyzing IMR data across different states, here we have chosen 2004 as the base year, comparing it with the latest IMR data, put out in September 2013 for the year 2012. An analysis suggests a clear urban-rural divide, with the situation in the rural areas remaining.

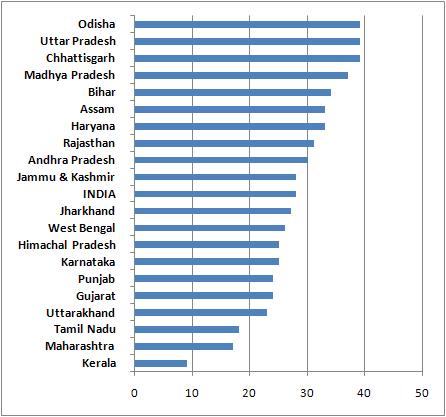

In rural areas of Gujarat, the 2012 data show, the state’s rural IMR was 45 per 1000 live births, just one point better the national average of 46. Bihar, long considered one of the worst states in social indictors, improved performance vis-à-vis Gujarat, with rural IMR of 44 per 1000; in 2004 it was 63 as against Gujarat’s 62. In 2012, backward Jharkhand, too, showed a better performance than Gujarat with by four points with rural IMR of 39. Kerala, as expected, topped the list with just about 13 rural IMR, followed by 24 Tamil Nadu, 30 Maharashtra, 30 Punjab, 33 West Bengal, 36 Uttarkhand, 36 Karnataka, 37 Himachal Pradesh, 39 Jharkhand, 41 Jammu & Kashmir, and 44 Bihar.

In fact, data suggest that, in rural IMR, Gujarat’s rural IMR ranking went down from 11th position in 2004 to 12th position in 2012 among 20 major states of the country, something that is conveniently overlooked by those who say that the state is “on the right track” as far as social indicators are concerned. As expected, the female IMR in the rural areas is worse than the male IMR, almost on lines with the national average. The national rural female IMR in 2012 was 48 per 1000 live births, while Gujarat’s it was 48. As for rural male IMR, the national average was 45 as against Gujarat’s 44. Even UNICEF has noted: “In the area of social development, one of the main challenges faced by the state is the high prevalence of child under nutrition, in addition to a slow reduction in Infant Mortality Rate (IMR) and Maternal Mortality Rate (MMR).” It adds, this factor has “drawn necessary attention of the Government and forms a critical partnership area for UNICEF.”

In fact, data suggest that Gujarat’s overall improvement in IMR has been mainly in the sphere of urban female IMR, which was a whopping 48 per 1000 live births in 2004 (against the national average of 40). It went down drastically to 25 per 1000 in 2012, an improvement of 23 points, perhaps the highest compared to any other state. Even then, in urban female IMR, Gujarat’s performance is worse than several states, including Kerala (10), Maharashtra (19) and Tamil Nadu (19). As for urban male IMR, Gujarat’s performance improved from 30 (national average 39) in 2004 to 23 (national average 26) in 2012. Better performing states here include Kerala (eight), Maharashtra (16) and Tamil Nadu (17). Had it not been for a sharp fall in urban female INR, Gujarat would have performed even worse.

In a paper written in 2009, “Maternal Health in Gujarat, India: A Case Study” a team headed by former professor of the Indian Institute of Management-Ahmedabad, Dilip V Mavalankar (see HERE), pointed towards the huge divide that appears to exist in Gujarat. The scholars say, “Standards of health infrastructure, equipment, logistical and administrative support differ according to the level of health facility. Higher-level facilities, e.g. medical colleges and district hospital, tend to have more infrastructure, equipment, and trained staff than do the CHCs and Primary Health Centres (PHCs) and subcentres. The general maintenance of the facilities influences the quality of services.”

The scholars add, “In many cases, the location of the facility is isolated at the outskirts of the village, with no approach-road, making it inaccessible in the monsoon. Government buildings have poor quality of construction, and maintenance is difficult due to lack of appropriate policy, money, priority, and cumbersome procedures, thus affecting the quality of services. The quality of infrastructure deteriorated over time; so, it is difficult to provide maternal health services in absence of adequate infrastructure. Fortunately, some improvement in infrastructure has taken place following the 2001 earthquake and funds coming under the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) since 2006”.

There has been considerable hoopla of late around how Gujarat’s health indicators, as found reflected in infant mortality rate (IMR), have suggested a “sharp improvement” recently. There have been reports which claim that there has been 33 per cent improvement in a decade. Indeed, while government officials, such as PK Taneja, state health commissioner, have pointed towards how Gujarat’s IMR has reduced to 41 in 2011 from 60 in 2001 (see HERE), even senior economists such as Prof Bibek Debroy, known to shower praise on the state’s “development model”, have been forced find such claims fake. Prof Debroy admits, “If Gujarat’s benchmark is better performing states, as it should be, and not all-India averages, obviously Gujarat needs to do better” (“Gujarat – The Social Sectors”, October 2012, Indicus White Paper Series). Infant mortality rate is defined as the number of children dying before the age of one. It is counted per thousand.

Despite this admission, unfortunately, Prof Debroy does not seek to provide inter-state comparisons to point towards where Gujarat stands vis-à-vis other states on IMR. What his study fails to mention is that, though Gujarat’s IMR has improved, it is not fast enough to take over states, who too have improved. The data suggest that things remain particularly pathetic in the rural areas. Gujarat’s overall IMR in 2004 was 53, five point lower than the country as a whole – 58. Half of India’s major states performed better than Gujarat. In 2012, for which the SRS released data in September 2013, suggest that Gujarat’s IMR was 38 four points lower than the all-India average of 42, suggesting the gap had narrowed, with the country’s average improving.

|

| IMR per 1000: Rural Gujarat ranks 12th among 20 states |

What provides credence to SRS is that it is based on dual record system. The field investigation under SRS consists of continuous enumeration of births and deaths in a sample of villages/urban blocks, followed by independent six monthly retrospective surveys by a full time supervisor. The data obtained through these two sources are matched. The last revision of SRS sampling frame was undertaken in 2004, one reason why, while analyzing IMR data across different states, here we have chosen 2004 as the base year, comparing it with the latest IMR data, put out in September 2013 for the year 2012. An analysis suggests a clear urban-rural divide, with the situation in the rural areas remaining.

In rural areas of Gujarat, the 2012 data show, the state’s rural IMR was 45 per 1000 live births, just one point better the national average of 46. Bihar, long considered one of the worst states in social indictors, improved performance vis-à-vis Gujarat, with rural IMR of 44 per 1000; in 2004 it was 63 as against Gujarat’s 62. In 2012, backward Jharkhand, too, showed a better performance than Gujarat with by four points with rural IMR of 39. Kerala, as expected, topped the list with just about 13 rural IMR, followed by 24 Tamil Nadu, 30 Maharashtra, 30 Punjab, 33 West Bengal, 36 Uttarkhand, 36 Karnataka, 37 Himachal Pradesh, 39 Jharkhand, 41 Jammu & Kashmir, and 44 Bihar.

|

| IMR per 1000: Urban Gujarat ranks fifth among 20 states |

In fact, data suggest that Gujarat’s overall improvement in IMR has been mainly in the sphere of urban female IMR, which was a whopping 48 per 1000 live births in 2004 (against the national average of 40). It went down drastically to 25 per 1000 in 2012, an improvement of 23 points, perhaps the highest compared to any other state. Even then, in urban female IMR, Gujarat’s performance is worse than several states, including Kerala (10), Maharashtra (19) and Tamil Nadu (19). As for urban male IMR, Gujarat’s performance improved from 30 (national average 39) in 2004 to 23 (national average 26) in 2012. Better performing states here include Kerala (eight), Maharashtra (16) and Tamil Nadu (17). Had it not been for a sharp fall in urban female INR, Gujarat would have performed even worse.

In a paper written in 2009, “Maternal Health in Gujarat, India: A Case Study” a team headed by former professor of the Indian Institute of Management-Ahmedabad, Dilip V Mavalankar (see HERE), pointed towards the huge divide that appears to exist in Gujarat. The scholars say, “Standards of health infrastructure, equipment, logistical and administrative support differ according to the level of health facility. Higher-level facilities, e.g. medical colleges and district hospital, tend to have more infrastructure, equipment, and trained staff than do the CHCs and Primary Health Centres (PHCs) and subcentres. The general maintenance of the facilities influences the quality of services.”

The scholars add, “In many cases, the location of the facility is isolated at the outskirts of the village, with no approach-road, making it inaccessible in the monsoon. Government buildings have poor quality of construction, and maintenance is difficult due to lack of appropriate policy, money, priority, and cumbersome procedures, thus affecting the quality of services. The quality of infrastructure deteriorated over time; so, it is difficult to provide maternal health services in absence of adequate infrastructure. Fortunately, some improvement in infrastructure has taken place following the 2001 earthquake and funds coming under the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) since 2006”.

Comments