By Rajiv Shah

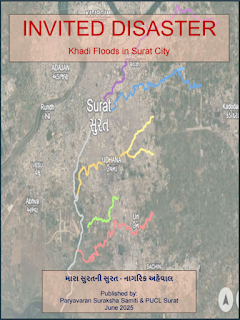

An action research report, “Invited Disaster: Khadi Floods in Surat City”, published by two civil rights groups, Paryavaran Suraksha Samiti and the People's Union for Civil Liberties, Surat, states that nearly half of Gujarat's top urban conglomerate—known for its concentration of textile and diamond polishing industries—is affected by the dumping of debris and solid waste, along with the release of treated and untreated sewage into the khadis (rivulets), thereby increasing the risk of flood disaster.

Conducted by two post-graduate students from Azim Premji University, Avadhut Atre and Buddhavikas Athawale, with assistance from environmental lawyer Krishnakant Chauhan, architect Sugeet Pathakji, environmentalist Rohit Prajapati, and urban planner Neha Sarwate, the study is based on field observations of the khadis passing through the South Gujarat town.

Using available secondary data, the study corroborates and confirms observed changes in these rivulets—intended as natural stormwater drainage channels for the urban area—through historical satellite images from Google Earth and interviews with stakeholders.

According to the study, authorized and unauthorized constructions, land reclamation along khadis, and resectioning and remodeling of khadi flows have severely compromised their capacity to carry stormwater. “In many areas in Surat city, smaller natural waterways have been levelled and converted into roads to facilitate traffic flow, overlooking the critical need for smooth stormwater drainage,” it asserts.

The study notes, “It can be said that the rainwater falling in city areas is unable to exit due to the ‘development’ of the city. The flooding of khadis impacts the eastern part of Surat city, affecting over 50% of Surat’s population. The textile trade also suffers during flooding, leading to economic losses.”

It estimates that khadi floods affect East Zone A, East Zone B, South East Zone, South Zone, and South West Zone, which collectively house approximately 43,75,207 of Surat’s total 82,32,085 residents.

More alarmingly, the study points out that the khadis are fed by discharges from sewage treatment plants. Moreover, numerous illegal outlets release both domestic and industrial effluents into the khadis. In fact, the city’s expanding periphery contributes untreated sewage into these waterways.

Containing a large collection of Google Earth images—compared from 2011 through 2025—of several rivulets such as Mithi Khadi, Koyali Khadi, Bhedwad Khadi, and Kankara Khadi, the study criticizes the Surat Municipal Corporation (SMC) for undertaking desilting as part of pre-monsoon preparedness “without due caution,” which, it claims, harms floodplain areas and reduces the capacity of the khadis to handle excess monsoon water.

One such example is a bridge over Mithi Khadi, now surrounded by a high wall over land that previously acted as a floodplain. Landfilling has raised the terrain above the natural flood level, pushing water toward other low-lying areas. “The obstruction around the bridge hampers smooth flow of water during the monsoon,” the report says.

The study further observes that construction and reclamation have reduced floodplain areas and the width of khadi stretches. Dumping and landfilling have drastically altered the elevation profile. At one site, a compound wall built in 2018 has resulted in the khadi being embanked by a concrete wall, shrinking its original area.

At another site, textile waste is directly dumped into the khadi, while accumulated solid waste and soil significantly hinder water flow. "A sewage outlet was observed discharging domestic and chemical wastewater—particularly from nearby units—into the khadi."

Focusing on Koyali Khadi, the report notes that road construction over it restricts natural water dispersion, causing severe waterlogging in the surrounding areas during monsoon. Particularly concerning is the ongoing project from Bhathena Naher bridge to Jeevan Jyot bridge, where the khadi is being fully concretized, drastically reducing its natural capacity.

The researchers warn, “With little to no space for excess water to flow or merge into other channels, this development poses a high risk of urban flooding and long-term stagnation during monsoons.” They add that the silt removed during desilting is often dumped on the banks, only to wash back into the khadi during heavy rain.

A comparative analysis of Google satellite imagery from 2011 to 2025 at Saniya Hemad village, located on Surat’s fringe, reveals “a noticeable alteration in the khadi’s flow pattern.” The 2011 image shows a naturally meandering khadi, while the 2025 image reveals a straightened course.

“Although this engineered modification may appear efficient in the short term, it shortens flow duration and reduces water retention, diminishing both ecological and flood-buffering functions,” the researchers highlight.

Near the Raghuvir Trade Market on Bhavani Road, earlier imagery showed a visible khadi flow, which by 2025 has vanished due to construction. Built-up structures over the khadi’s path have obstructed this natural drainage, increasing the risk of urban flooding.

Examining the impact of development on water flow, the study notes that the Bhedwad Khadi followed a wider, more continuous path in 2011. By 2025, construction near Bamroli cricket ground has narrowed its course and reduced its flow capacity.

It adds that near the Dindoli Water Treatment Plant, the Bhedwad Khadi’s course has been significantly altered and straightened for aesthetic reasons, severely compromising its natural flow.

In the area around Om Industrial Estate in Saroli, researchers found the khadi’s path constantly shifting. Its older flow, once almost gone, reappeared in 2025 imagery. “Taming a khadi and constructing concrete embankments drastically alters its natural behavior,” they say, “leading to unintended consequences such as heavy silt accumulation.”

At the Kankara biodiversity park, a 2016 image shows the right bank of Kankara Khadi concretized with a diaphragm wall. The park and a road were built by raising the land level. By 2025, both banks have diaphragm walls, eliminating the khadi’s natural meander and floodplains.

Further, near Gabheni village on the city outskirts, the khadi’s course has changed due to drastic land use alterations. “Legal and illegal shrimp farms have contributed to this change. Industrial waste dumping here has led to severe water and soil pollution,” the report adds.

During fieldwork, most respondents identified poor stormwater drainage as the key issue. “Drains are too narrow, broken, or absent in some areas,” the study says. These are further clogged by solid waste, particularly plastic, discarded by residents and industries.

Shopkeepers highlighted the lack of regular SMC clean-up. They reported repeated losses during monsoon, as inventories are damaged and earnings suffer. Businesses shut down for days due to prolonged water stagnation.

In low-lying markets, encroachment on khadi banks and lack of flood management lead to backflow during heavy rainfall. Locals noted a rise in unseasonal rains, aggravating waterlogging. Builders acknowledged that unplanned urbanization has severely disrupted the city’s hydrology.

“Residents, particularly near Koyali and Mithi khadi, emphasized the interlinkage among the khadis. When Kankara Khadi overflows, water backflows into Mithi Khadi, causing flooding in homes. This is devastating in low-lying areas with poor housing,” the study notes.

“Loss of income is the most immediate impact,” residents report. For shopkeepers and daily wage earners, flooding forces closures for several days. One woman said, “I am the sole earner. When it floods, work halts for 4–5 days. My shop remains shut for a week. We then rely on SMC for food and water.”

Mobility is another major issue. Waterlogged streets restrict access to work and healthcare. Children miss school, and both public and private transport becomes unreliable due to submerged roads.

The report concludes by stressing health risks. Waterborne diseases like fever, diarrhea, and skin infections, along with vector-borne diseases like dengue and malaria, increase after khadi floods. Residents mentioned rising medical expenses, adding strain to financially stressed households. “Stagnant water near homes, especially by khadi banks, becomes mosquito breeding grounds, worsening health conditions,” it warns.

Comments